Many people in ministry and others could sympathize with the declaration of Rev. John Newton (1725-1807), author of the famous hymn, Amazing Grace, that he had:

“seldom one hour free from interruption, letters that must he answered, visitants [visitors] that must be received, [and] business that must be attended to. I have a good many sheep and lambs to look after, sick and afflicted souls dear to the Lord: and therefore, whatever stands still, these must not be neglected.”

Yet despite this busy and largely self-directed schedule, Newton also recognized the claim God had on his time in an unpredictable way. Thus, elsewhere he wrote:

“When I hear a knock at my study door, I hear a message from God. It may be a lesson of instruction: perhaps a lesson of patience: but, since it is his message, it must be interesting.”

We can all, perhaps, readily identify with this delineation of busyness, whether of the scheduled or unexpected kind. In the public service dimension to my work as a theology librarian, for instance, interruption is an expected and normative occurrence in servicing the information needs of patrons. Simply put: I am there to be interrupted!

Yet on a wider canvas, how are we to regard interruptions and how might we view them in the context of a godly perspective on time?

If we accept Christ as lord of our lives, this also means that he is lord of our time and its allocation and disposition. In the words of the psalmist, “My times are in your hands” (Psalm 31: 5a). All too often, however, we conduct our affairs and speak of the stewardship of our time as if we already have the right to, or aspire to, a rigid, total control of it.

I would suggest that we need to view our use of time in two ways each reflective of an attribute of God’s nature. On the one hand, because our God is a God of order, reflected in the orderly way in which the world was created (as recorded in Genesis 1), we need to reflect that divine sense of order in the way we carry on our lives, our work schedules, our family times, and our recreation. On the other hand, our God is a God of surprises and a purveyor of the unexpected. Because of this divine attribute we should expect the unexpected in our lives, even in the midst of our orderly existence! In such circumstances, we have to patiently relinquish our hold on order, predictability, and control, and allow the Lord to break in and interrupt.

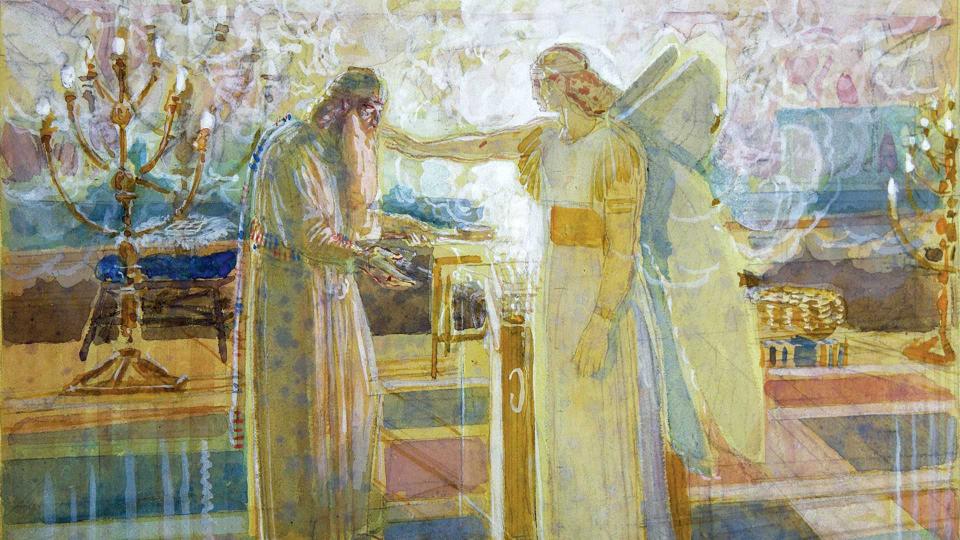

Here the situation of Zechariah (Luke 1: 1-20) is instructive. He and his wife Elizabeth were members of a religious élite with service to God at the centre of their lives. Yet they had their burdens to bear in terms of childlessness, unanswered prayer, and advancing years. Zechariah followed a rigid and predictable routine as a priest in the temple. This routine was interrupted when the lot fell to him to enter the sanctuary to offer incense to the Lord (vv. 8-9). This would have been a time of keen awareness when God's presence would have been felt more closely than usual. But this high point in the religious routine is shattered by the announcement from the angel that Zechariah and his wife are to have a son. Amid the familiarity, ritual and predictability of his religious duties, Zechariah was surprised by God's intervention and given a life-changing experience of hope and transformation.

Another manifestation is prayer, the central activity of the Christian. In our private devotional time we naturally aspire to an atmosphere of silence and stillness and the dispelling of distractions, in order to facilitate our prayer. However, if we get overly anxious about eliminating all noise and distractions, such anxiety can in itself become a barrier between ourselves and God. In such circumstances, it is important to be mindful of the fact that given the fact of the Incarnation, the Word did become flesh, and, as a consequence, God can speak to us even in the activity and noise around us. Thus, a prayerful stance or disposition can involve taking account of such circumstances around us.

A nineteenth century author, John Stuart Mill, advanced a definition of life as “the permanent possibility of sensation.” Christians might legitimately substitute "sensation" with “interruption”. We live with a disposition of waiting, of living in hope, faith, and perseverance. At the end of time we await the return of Christ, and while we don't know when that will be, we do know that it will be the greatest “interruption” of all. In anticipation we say: “Come Lord Jesus. Come.” Amen. Alleluia.