As part of Wycliffe College's commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, Wycliffe College faculty and faculty from the Toronto School of Theology tell the stories of key personalities of this momentous movement in history. New biographies are added throughout the Fall of 2017.

John Smyth (1570-1612) - The Rev. Dr. Peter Holmes

This biography is written by the Rev. Dr. Peter Holmes (Wycliffe '86), Pastor at York minster Park Baptist Church. It also appears as the editorial of the November 27, 2017 edition of Wycliffe College's Morning Star newsletter.

John Smyth, (1570-1612). By the time John Smyth, who is widely regarded as the founder of the Baptist Church, was born, Luther, Zwingli and Calvin were all dead and John Knox was approaching the end of his life. John Smyth sensed a call to ministry and studied at Cambridge after which he was ordained into the Anglican priesthood in 1594. Smyth served in both Cambridge and Lincolnshire, but before long some of his contentious views landed him in prison. After that ordeal he abandoned the priesthood and for a short time took up the study of medicine. By 1606 Smyth had left the Church of England and formed a ‘Separatist’ congregation in Gainsborough.

Like the Puritans, the Separatists took exception to alleged abuses in the state church, but no longer believed in trying to purify the church from within. They came to believe the church is a creation of the Holy Spirit rather than a creation of the state and that the essence of belonging was birthed through a personal belief in Christ. Separatists also moved away from hierarchical leadership towards a more congregational form of church governance.

Though separatists would become very influential under Oliver Cromwell during the years of the Commonwealth, (1649-1660) and would eventually survive, they were heavily persecuted during the reign of King James 1. Smyth’s underground church in Gainsborough grew so rapidly that it could no longer function in secret and so in 1608 Thomas Helwys, a wealthy lawyer in the congregation, financed passage for members of the church, including Smyth and himself, to Holland. It was while in exile in Holland Smyth and Helwys came in contact with the Mennonites. Smyth, whose aim was to align the church with the model of the early church in the Book of Acts, responded positively to the Mennonite teaching on Baptism as an expression of belief, obedience and testimony, rather than as an instrument of salvation to be imposed on infants.

Meno Symons, the founder of the Mennonites had been baptized as a believer in 1536, so Smyth was far from the first to reintroduce the idea of believer’s baptism, but the Mennonites baptized by pouring as did Smyth initially. Smyth was the first to submit to believer’s Baptism and then baptized the rest of his flock. Initially this was done by pouring, but it would not be long before his congregation was practicing Baptism by immersion. Helwys led most of the congregation back to England where they formed the first Baptist congregation in 1611. However, Smyth was never to return to England.

Smyth had other distinctive notions including the belief that everything offered in worship had to be of the Holy Spirit and therefore extemporaneous offerings were preferred over anything written by human hands. Smyth was very familiar with both the Book of Common Prayer of 1549, and with the early English translations of the Bible, but he was so suspicious of the works of human hands that their use was not permitted in worship. Instead Smyth preached from the Hebrew and Greek texts offering simultaneous translation in his sermons.

In other areas he was truly radical in his reforms. In terms of polity he gave authority to the congregation rather than the clergy and in terms of religious freedom he insisted that it be extended beyond separatists and non-conformists to include Muslims.

As a lawyer Helwys rejected the Mennonites teaching against oath taking as well as their pacifism. Both Smyth and Helwys struggled with elements of the early Mennonite Christology, but after Helwys left for England, Smyth grew ever closer to the Mennonites with whom he formally joined before the end of his life in 1612 at the age of forty-two. Though his life was short, his legacy as the founder of the first Baptist Church and as an early advocate of religious liberty, congregational autonomy, the freedom of conscience and Biblical authority was profound and significant.

Biographies of other reformers:

John Wycliffe (1330?-1384)

This biography is written by Stephen Andrews, Principal of Wycliffe College. It also appears as the editorial of the September 11, 2017 edition of the Morning Star newsletter.

At its inception in 1877, our college bore the name Protestant Episcopal Divinity School. An early historian of the college called it a ‘cumbrous title’, and I suppose we should be glad that there was a movement to change the name. The term ‘protestant’ carries connotations that require careful explanation (in much the same way as ‘evangelical’), and besides, it is never a good idea for a church or an institution to define itself primarily by what it is against.

In 1882 a proposal came forward that the new building on Hoskin Avenue should take the name of Wycliffe. It is not clear in the records where the proposal came from. It is worth noting that our sister institution, Wycliffe Hall in Oxford, also founded in 1877 in response to an ascending ritualism, settled on this name. The Manchester Guardian was disapproving of the decision, calling the proto-Reformer’s views ‘very wild and revolutionary’. But one can imagine that this might have struck nineteenth-century adolescent protestant ears as being a noble commendation.

So who is this John Wycliffe, whose moniker we bear? Known among the sixteenth-century reformers as the stella matutina, or ‘morning star’, he was a fourteenth-century English priest and academic who was widely regarded as the herald of the Protestant Reformation. A casualty of Middle English spelling conventions, the name variously appears ‘Wyclyf’, ‘Wyclif’, and ‘Wiclef’, etc. As to his appearance, he is depicted in at least four places at the College (see if you can locate them), and today I think he might be mistaken for a hipster. As an institution in the nominal family tree we are regularly confused with Wycliffe Bible Translators and are frequently called ‘WHY-cliff’. It is tempting to wish that we might have been attached to a better known and more pronounceable ecclesiastical figure. But John Wycliffe is an appropriate and worthy pater academic.

A Yorkshireman by birth, Wycliffe went up to Oxford in 1345 and remained there until 1381, teaching both philosophy and theology. His writings did indeed contain views that were taken up by revolutionaries. He maintained, for instance, that the authority of the Church’s leadership depended on the personal righteousness of the leader. ‘No-one in mortal sin is lord of anything’, he wrote, and this included the pope. Moreover, he rejected the idea that the Church could grant absolution for sin. Only God can forgive, he said, and only God knows whether or not a sinner is truly contrite. Therefore, oral confession (i.e., to a priest) is unnecessary.

As you may imagine, these viewpoints were unpopular enough, but chief among the twenty-six errors and heresies for which he was condemned in 1382 was his understanding of the Eucharist: ‘That the substance of material bread and wine remains after the consecration in the sacrament of the altar’. Wycliffe held what might be described as a figurative understanding of the Eucharist. Citing Augustine and Jerome as authorities for his view, he claimed that at the words of consecration ‘the nature of the bread is not destroyed, but is exalted to a worthier substance’. Such opinions were a direct challenge to the Fourth Lateran Council’s declaration that in the sacrifice of the Mass the bread and wine become in reality the body and blood of Christ.

Although it would be a mistake to think of Wycliffe as a reformer in the same way we regard a Cranmer or a Latimer or a Tyndale (he was, after all, a medieval man), his doctrines resonate with what the Reformers taught, and they continue to challenge us today. But there is one more reason why he is still venerated by the College that bears his name.

John Wycliffe was nicknamed Doctor Evangelicus because of his views about the Bible. He took the Bible, and especially the New Testament, as the only trustworthy source of Christian doctrine and practice, and he taught that our ecclesial institutions ought continually to be measured against the practices of the early Church. Towards the end of his life he spent the majority of his time commenting on Scripture, and he initiated an ambitious project to translate the Bible into English. It was a pioneering work executed by his followers in the years after his death. His ‘Five Rules for Studying the Bible’ are still valuable: 1. Obtain a reliable text; 2. Understand the logic of Scripture; 3. Compare the parts of Scripture with one another; 4. Maintain an attitude of humble seeking; and 5. Receive the instruction of the Spirit.

In the Prayer Book calendar John Wycliffe is remembered on 30 December, a date close to his death on New Year’s Eve 1384, while in the Episcopal and BAS sanctorale he is celebrated on 30 October. I am proud to be associated with an institution bearing his name. May his reforming spirit live on in our community for the glory of Christ and the welfare of his Church.

Jan Hus (c.1372 – 6 July 1415)

This biography is written by Sean Otto. It also appears as the editorial of the September 18, 2017 edition of the Morning Star newsletter.

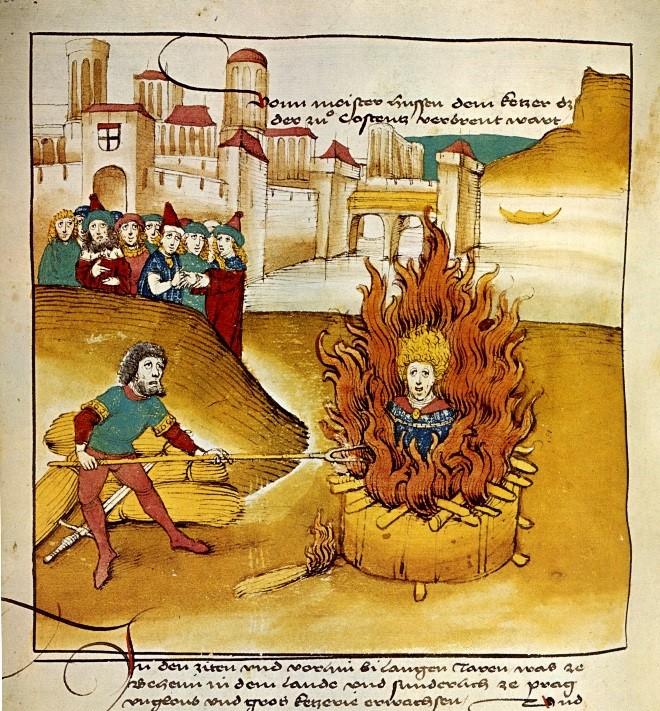

Image: Hus burned outside the walls of Constance, 6 July 1415 (Spiezer Chronik, 1484/5)

Jan Hus was born (probably) in the village of Husinec, in the southern reaches of Bohemia, one of the Czech lands in Central Europe in what is now the Czech Republic. He was educated at the recently founded Charles University at Prague, which had been established in 1348 by Charles IV, King of Bohemia and King of the Romans, the first such foundation east of Paris and north of the Alps. Here, he completed a bachelor of arts (1393) and master of arts (1396) and studied theology, writing a commentary on Peter Lombard’s Sentences the standard medieval textbook of theology, between 1407 and 1409. It was here that he encountered and read the works of John Wyclif, about whom you learned something last week. Wyclif’s philosophical ideas, his realism and logic, were especially influential in Prague, as were his reforming ideals, which found ready ground among a nascent group of Czech reformers who had been influenced by earlier thinkers such as Jan Milič of Kroměřiž (c. 1325 – 1374) or Matthias of Janov (c.1350 – 1393), who denounced abuses among the clergy and emphasized preaching and the place of the Bible in Christian thought and practice. Wyclif’s works were copied, both in Prague, where Hus himself copied some of them to earn his keep as a young student, and in England, where Czech scholars visited in order to bring back copies, along with stone chips from Wyclif’s tomb at Lutterworth.

One of the reasons that Wyclif’s works met with such approval had to do with trends in late medieval philosophy and tensions between German and Czech scholars within the university. Bohemia in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was part of the Holy Roman Empire, and Prague was an Imperial city. The Empire was multi-ethnic, but Germans predominated many aspects of life and government, and German students at Charles University were no exception during the early decades following the university’s foundation. The Czech scholars, probably about a quarter of the student body in the 1380s, resented this. The Germans were also followers, philosophically, of the nominalist school of thought whose most famous proponent was William of Ockham. Nominalism was cutting-edge and popular, and of great influence through the Reformation and beyond. Czech scholars at Charles University tended to be, like Wyclif and Hus, more conservative, realist and Augustinian in their thinking. Wyclif’s bold and robust attacks on nominalism were thus a very welcome tool to use against the Germans, who were finally ousted from power in 1409 by the Decree of Kutná Hora, issued by the king of Bohemia, Wenceslas IV, which gave the Czechs a dominant vote in university affairs.

It was during this time when Wyclif’s influence was on the rise at the university, that Hus was appointed rector at Bethlehem chapel (1402), and later rector of Charles University (1409 – the first rector elected under the new rules established at Kutná Hora).

As rector of the university, Hus fought for the right of the scholars there to study the work of Wyclif, which had fallen under ecclesiastical censure the previous year when the Archbishop of Prague, Zbyněk of Házmburk (c.1376 – 1411), gave in to the pressure exerted by the German scholars of the university. Hus argued that scholars should be able to read books that contained truth, even if this truth were mixed with heresy, otherwise scholars would have to give up the study of Aristotle, and even the study of the Old Testament. From these disputes over the study of Wyclif, which went as far as the papal curia, Hus became entangled in the legal proceedings that would eventually take his life, and became associated with heresy in the eyes of the ecclesiastical hierarchy.

During this upheaval centered on the university, Hus continued to serve at Bethlehem chapel. Bethlehem was an enormous church in Prague which could hold as many as 3000 people. There Hus spent his time preaching in Czech, twice on each Sunday and each saints’ days, for twelve years, for a total of approximately 3000 sermons. Largely on account of Hus’ preaching, Bethlehem became the center of a reform movement focused on correcting abuses among the clergy, principally simony, or the buying and selling of church offices.

Hus also spoke out about indulgences, which he thought were being abused for temporal gain by the clergy and members of religious orders (monks and friars). In this, he opposed King Wenceslas who favoured them, and so Hus retreated from Prague to the countryside to avoid conflict and entanglement with the king and his supporters. Hus followed Wyclif in rejecting the church’s practice of indulgences, and like him, wrote a treatise On the Church (De ecclesia), in which he argued passionately for the reform of the church by secular lords.

Where Wyclif and Hus diverged was over that most important of doctrines to late medieval Catholic Christians – the Eucharist. For Wyclif, the Roman teaching on the Eucharist, the doctrine of transubstantiation (that the bread and wine become the substance of Christ’s body and blood under the appearance of the bread and wine), was idolatrous and unbiblical. Hus would not follow Wyclif into a rejection of transubstantiation, but that does not mean he agreed with Roman teaching on the Lord’s Supper. By the fifteenth century, it had become common practice that the laity would receive only the bread during mass, ostensibly to prevent them from unwittingly profaning the very blood of Christ, which was inconveniently easy to spill on the floor or dip one’s mustache into. Hus, although he had been reticent to express strong support for the reception of the Eucharist in both kinds (sub utraque specie – under both kinds, for which we get the term Utraquist), did so more emphatically in the weeks before his death. It was, in fact, Jakoubek of Střibro (d. 1429), Hus’ fellow reformer and colleague at Charles University, who introduced the liturgical reform which extended the chalice to the laity.

For his association with Wyclif, and for his participation in reform efforts in Prague, Hus came into sharp conflict with the ecclesiastical hierarchy. The situation was exacerbated by the continuing papal schism, which had begun in 1378 with the disputed elections of Urban VI (of Rome) and Clement VII (of Avignon). Europe was divided along political and confessional lines, with some kingdoms swearing allegiance to Rome and Urban and others to Avignon and Clement. The schism became even worse after an abortive attempt at a conciliar solution ended with the election of Alexander V at the Council of Pisa in 1409, adding a third pope to the division and confusion. Who exactly was in charge was a live and important question. Finally in 1414, Sigismund, King of the Romans, decided that enough was enough, and called for a general council to meet at Constance, a city in the north of what is now Switzerland, between Zürich and Munich. The Council had three aims: to end the schism, to eradicate heresy, and to reform the church “in head and members.” Hus was invited to the council, and given safe passage by Sigismund.

It is unclear precisely what Sigismund’s intentions were in issuing the safe conduct, but it seems clear that Hus anticipated a debate over the contested issues. Instead, upon arrival in Constance, he was placed under arrest and charged with heresy, for which he stood trial before the council fathers. While Hus treated the trial as a disputation, offering arguments for his position on several topics, his judges simply viewed this as contumacy, since he had technically been under investigation since his days defending the study of Wyclif’s works in Prague. The judges found him guilty of the same heresies for which Wyclif had been found posthumously guilty at an earlier session of the council. Hus was relaxed to the secular arm, that is, he was handed over to the civil authorities, and he was burned at the stake outside the city walls on 6 July 1415. His supporter Jerome of Prague was likewise put to death at Constance, and an order was issued to have the body of Wyclif dug up, ritually stripped of priestly office, burned, and the ashes scattered, the council fathers being sure to cover all of their bases.

Hus’ death at Constance galvanized the Czech reform movement, which took root among nobles and commoners alike in Bohemia, and an influential group of radical reformers formed at Tábor, in the south of Bohemia, by 1420. The central issues in the conflict were the extension of the chalice to the laity, freedom to confess the divine word, secularization of church property (removal from the control of the church), and chastisement of mortal sins. The situation devolved into armed conflict, which lasted for 14 years. A handful of crusades were called against the Hussites, but these were defeated by the innovative military commander Jan Žižka (One-Eyed Žižka), who used field artillery and war-wagons to ward off the armies of King Sigismund and the various crusades launched under the auspices of the reunified papacy. Infighting among moderate and radical parties within the Hussite fold continued when they were not fighting crusading armies, which the Hussites were able to hold off even after the death of Žižka in 1424. By 1434, the moderate Hussites had won out, and were able to make peace with the Roman church, and gain watered-down concessions, which at least allowed the laity to receive the chalice at mass, but only in Bohemia.

Much like Wyclif, Hus’ influence on the movement which bears his name is somewhat contested and ambiguous. While he was certainly an influential and important preacher for reform, his influence on the Hussites does not seem to have extended to the formulation of doctrine. He is most famous for his martyrdom at Constance, and as a symbol of the reform movement. His influence on the Reformation is likewise tenuous. While he anticipated many of Luther’s arguments about indulgences, Luther did not know Hus’ work on them until after he had already formulated his own opinions, much as Luther enjoyed Hus’ works once discovered. The Unity of Czech Brethren, a movement that grew out of the Hussite reforms of the 15th century, stayed strong, if small, into the 16th century, and even into the 17th, when they were forced to flee to Moravia by Counter-Reformation politics, but this was the only movement that broke with Rome.

This does not take away from the importance of Hus; he was a keen reformer, a tireless preacher, and a concerned pastor looking after the best interests of his flock. More than this, he paid the ultimate price for what he believed was right, and true, and good, and maintained his faith in the face of death at the stake. I can imagine more than a few of us are able to say with Luther that “We are all Hussites without knowing it,” and can only hope to show the same resolve in our own faith.

Martin Luther

This biography is written by David Demson. It also appears as the editorial of the September 25, 2017 edition of the Morning Star newsletter.

Luther in his younger years was in persistent anxiety over his relationship to God. A turning from this anxiety began as he, having become a professor of Scripture, immersed himself in the study of the Psalms, Romans and Galatians. In 1518, after having engaged with these biblical books, he wrote some theses, with explanations of them, for a disputation in Heidelberg. In this material Luther presents a synthesis of what he had learned from his biblical studies to this point, and this material stands as a basis for his theology and preaching throughout his life.

In the theses (particularly theses 19-24 of the Heidelberg Disputation), Luther speaks of one who, while calling her or himself a theologian, doesn’t deserve the name because “…that person looks upon the invisible things of God as though they were clearly perceptible in those things that have actually happened (or have been made).” What does Luther mean by ‘the invisible things of God’? [He is certainly being ironical when he speaks of this pseudo theologian ‘looking at’ the invisible things of God]. And what does he mean that this supposed theologian thinks they are clearly perceptible?

Luther tells us in his explanation of the thesis, that by the ‘invisible things of God’ he means God’s attributes: power, holiness, wisdom, and righteousness. Since, according to Scripture, these attributes do belong to God, Luther is not denigrating them. What he distains is the way the fake theologian speaks of these attributes. This supposed theologian [Luther now refers to this one as a theologian of glory], looks about him or herself in the world and sees a bit of what that person thinks to be human wisdom, human righteousness, human holiness and constructs a picture of God as the perfection of these elements to be found in the world. In sum, the nature and way of the world reflects the nature and way of God.

In distinction from this the true theologian is focused on the cross of Christ and suffering. Indeed it is Luther’s statement that “the cross and suffering [the cross] are our theology” that has prompted the characterization of Luther’s theology as a theology of the cross.

Luther contends that God in undergoing the cross crucifies the wisdom of the wise; that is, the supposing that we see God reflected in the way of humans and in the nature of the world. The true theologian recognizes in the cross, God’s power in its powerlessness, God’s righteousness in its unrighteousness, God’s holiness in its profanity, God’s wisdom in its foolishness.

Luther in thesis 20 avers that since God reveals Himself in the humility and shame of the cross, theology that does not begin in the cross is not Christian theology at all. While Luther indicates that some knowledge of the invisible God might be gained from observation of the nature of the world and the way of humans in the world, he declares that such knowledge will be misused by anyone whose point of departure is not the place where God makes Himself visible (to faith) – namely, in the suffering, the humility and shame of the cross of Christ. “True theology and recognition of God are in the crucified Christ,” Luther proclaims.

Why do many begin their (so-called) theology with the nature of the world and the way of the human? In thesis 21 Luther remarks that these people are those Paul calls ‘enemies of the cross’ (Phil 3:18). For they hate the cross and suffering [the cross] and love what they consider their own ‘holy achievements’ and the ‘supposed glory’ of them. They call the good of the cross evil and they call the evil of their achievements good. (The evil of these achievements is the supposition that by them we make ourselves righteous, whereas by them we in fact make ourselves self-righteous and thereby place ourselves at odds with God.) God can be found only in the cross and suffering the cross.

At this point in the theses of the Disputation, Luther refers back to the first few theses. The pseudo theologian of glory thinks that by our own power we can perform acts which enable us to reach God; he/she thinks by our own power we can will to do what God wants us to do; he/she thinks we can know by our own powers who God is and what God wants us to do. The Gospel declares to us that none of these things is true. Where the Gospel hits home in us, we are divested of these false ways of thinking and acting. We suffer a divine action, a crucifixion of who we have been and are ever tempted to be again. God crucifies in us our self-constructed way by which we think we know Him; crucifies our way of willing what we think is God’s will for us; crucifies what we think are the acts by which we reach Him.

In all of this, Luther is not implying that God is the enemy of His human creatures. God is for us. Luther, following Paul, speaks of the Son of God humbling Himself, receiving suffering and death with us. And as the Father vindicates the humility of the Son, by raising Him from the dead, so too He raises and vindicates all those whom His Son has put on and who by faith put Christ on, and thereby bestows upon them not only new but also eternal life.

Thomas Cajetan, Theologian and Reformer (?)

This biography is written by Professor Joseph Mangina. It also appears as the editorial of the October 2, 2017 edition of the Morning Star newsletter.

Francesco de Vio of Gaeta, also known as Cardinal Cajetan (1469-1534), was a talented theologian, philosopher, bishop, and biblical commentator. From 1508 to 1518 he was Master General of the Dominican Order, also known as the Order of Preachers. If not an inspiring leader, he was at least competent and honest and concerned to correct abuses that had crept into the Dominicans over time. Anglicans will be interested to know that in the early 1530’s he was asked his expert opinion on a certain English king’s request to have his marriage annulled. Cajetan argued that the relevant Old Testament texts did not support Henry’s claim that his marriage to Catherine had been invalid. Cajetan was certainly a conservative and supporter of traditional Catholic teaching, but he was by no means a reactionary. Although trained in scholastic methods, he knew enough about the new humanism to insist that interpreters should refer to texts in their original languages wherever possible.

As a theologian, Cajetan is best known for his commentary on Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologia; indeed for a long time his was the official Catholic interpretation of that great work. In the twentieth century Cajetan’s reading of Thomas came in for heavy criticism, not least from Étienne Gilson, who founded the Pontificial Institute for Medieval Studies here in Toronto. The criticism is that Cajetan taught a rather static and unbiblical substance-ontology, treating both creatures and God as “kinds of thing,” rather than seeing creatures as existing in God by way of participation. Theologians such as Gilson and Henri de Lubac thought Cajetan had badly misread Thomas. Intellectual fashions change. Some Catholic philosophers now think Cajetan was more right than Gilson. However that may be, it is undoubtedly true that he was a man of immense intellectual gifts, well equipped for his encounter with Luther at Augsburg in October, 1518.

The Imperial Diet of Augsburg initially had nothing to do with the “case of Luther.” Rather, it had been convened to consider Pope Leo X’s ambitious and potentially expensive plan to create a united front against the Turkish threat in eastern Europe. Cajetan, who was nearing the end of his term as General Master of the Dominicans, was sent to Augsburg to plead Leo’s cause with the gathered princes and nobles of the Empire. At the same time, however, the controversy stirred by Luther’s teaching about indulgences was slowly making its way through official channels in Rome. Since Cajetan was going to be in Germany anyway, it was thought good to have him interview the troublesome monk and remand him to Rome if necessary. This story is told very well by Jared Wicks S.J. in his book Cajetan Responds, which offers translations of Cajetan’s major writings dealing with Reformation issues.

Protestant paintings of this event (like the one below) tend to depict it as a dramatic clash between the heroic young rebel and the representative of the old, corrupt, official church: “Here I stand, I can do no other!”

But Luther did not say that at Augsburg, if he said it at all. That story belongs to the 1521 Diet of Worms. The meeting at Augsburg was much less dramatic. It revolved around two fairly technical questions in scholastic theology, which Cajetan had identified as receiving problematic answers in Luther’s writings. The first question—not surprisingly—had to do with indulgences. The most influential theological accounts of indulgences said that the church was authorized to grant them on the basis of the “treasury of merit,” acquired by Christ and the saints—a kind of infinite bank account of grace. Luther had a far more limited view of indulgences. He didn’t deny the church could granted them, but saw this simply as part of the church’s normal exercise of penitential discipline. We can see here an early hint of Luther’s ongoing battles with Rome over Papal authority.

But it was the second question that was the more interesting, and fraught with theological difficulties. It might be put this way: when you go to confession and the priest absolves you, how can you know that the absolution has been effective? That your sins are in fact forgiven? Luther said: you can know this because faith trusts in God’s promise! Faith clings to Christ, who is present to me in the sacrament and in the confessor’s words absolvo te (“I absolve you”). Here God humbly stoops down to meet me and forgive me my sins. What could be more certain than that?

The trouble was, Cajetan did not see it that way. He saw Luther’s insistence on receiving the sacrament in faith as an unheard-of innovation, one that essentially told people they had the power to absolve themselves—to be certain of their status before God. As a good Thomist, Cajetan had a much more restrained understanding of faith as assent to divine truth and the church’s teachings. It is fair to say that he had never encountered anyone who talked about faith quite the way Luther did, using the Pauline idiom of radical trust in the gospel of Christ. No doubt Cajetan read his Bible, but he did not “speak Bible” as Luther had learned to do through his study of the Psalms and other biblical texts.

Before we rush to criticize Cajetan, it is important to recognize that he had a point. The subsequent history of Protestantism is full of instances where people arrogantly claim all kinds of things about themselves on the grounds that they “have faith.” Faith, so understood, is about the self and its freedom from all worldly obligations, including the obligation to serve the neighbour. Hence Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s argument in Discipleship about the dangers of “cheap grace,” amounting to a permission to keep on sinning. From this perspective, one can understand why Cajetan was cautious about Luther’s innovative teaching. He rightly saw that talk about faith too easily becomes a covert way of talking about the self. By his own lights, he was being utterly traditional and theocentric.

Of course, Luther also thought he was being theocentric. The certainty he found in penance was not based on his own estimate of himself, but on the promises of God. It is God-in-Christ of whom we can be certain; therefore the penitent can go away with a joyful heart and an eagerness to serve the neighbour. Faith means union with Christ through glad acceptance of the gospel. It is God’s promises we count on, and not our own strength—not even the strength of our faith. “Lord, I believe; help thou my unbelief.”

Luther, I think, stood on good biblical ground with his teaching about divine promise and the utter trustworthiness of divine promise, available to us in the Word and the Sacraments. This is an aspect of Luther’s doctrine we should have no difficulty celebrating in this Reformation anniversary year. But we should also be mindful of the ways in which that doctrine can be misunderstood. In many modern churches, Catholic as well as Protestant, the word “faith” is often employed in ways the Reformers would have found unrecognizable. It can frequently sound like a vague trust that things will “come out all right,” or (even worse) as the power of positive thinking. Both Cajetan and Luther would have been horrified. Let us learn from Luther to believe boldly in the promises of God in Christ, and from Cajetan to temper our boldness with the humility that comes of a life ordered to the love of the triune God.

Jeanne d’Albret, Huguenot Leader, and the French Wars of Religion

This biography is written by Professor Alan Hayes. It also appears as the editorial of the October 10, 2017 edition of the Morning Star newsletter.

Celebrating the Reformation, as we’re doing in this symbolic anniversary year, is double-edged. There’s much to affirm, but much to regret.

On the one hand, I’m grateful for the leadership of women in the religious affairs of the Reformation period. Who was more influential, in the second half of the sixteenth century, than Elizabeth, Protestant Queen of England, and Catherine de’ Medici, Catholic regent of France? Not that their leadership was always, or maybe even usually, wise. But, if nothing else, their example sparked some fresh engagement with Scripture, challenged unhelpful views on gender, and opened opportunities for later Christian women.

On the other hand, the militarized religious hostility of the period, Catholic versus Protestant, is deeply repugnant to me. Wars of religion ravaged Europe, inflicted immense destruction and human damage, and alienated many modern people from all religious claims.

Which brings me to Jeanne d’Albret (1528–1572), Queen of Navarre and leader of the Huguenots (French Protestants influenced by the Reformed theology of John Calvin) during the first three French wars of religion.

Navarre, an independent kingdom in those days, straddles what’s now southwest France and northwest Spain. Jeanne’s authority also extended over much of Aquitaine to the north (it was called Guyenne then), an area that includes Bordeaux and the port town of La Rochelle, which prospered from shipping Bordeaux wine to the English.

Jeanne was the daughter of Marguerite of Angoulême, a well educated, cultured, and religiously devout woman of the Renaissance. She has been called the first modern woman. Marguerite was celebrated in her day, or notorious, for her poem “Mirror of the Sinful Soul,” in which she mystically identified with a succession of women in Scripture who experienced God’s grace. The poem was condemned by the theologians of the Sorbonne as heretical, but, as it happens, Marguerite’s uncle was king of France, so, ‘nuff said. The future Queen Elizabeth of England, at the age of eleven, translated Marguerite’s poem into English as a gift for her Protestant stepmother, Katharine Parr.

With such a mother, Jeanne grew up Biblically literate, in touch with God, high-spirited, and resolute.

In 1548, for dynastic reasons, she married the handsome but philandering Antoine de Bourbon. In 1555, on the death of her father, she inherited the throne of Navarre, which she chose to share with her husband.

For various reasons, lower Navarre and Guyenne had developed Protestant sympathies. In particular, La Rochelle was a Reformed stronghold. And Reformed churches were springing up all across France, planted by missionaries organized from Geneva. In 1559, the first national Reformed synod was held in Paris. Jeanne was open to the Reformed faith, and many of her advisers and nobles encouraged her in that direction. John Calvin wrote her frequently. An eminent young Geneva theologian, Theodore Beza (soon to be Calvin’s successor), came to visit her. She was touched, too, by the persecutions of Reformed believers.

Finally on Christmas day 1560 the Queen attended a Reformed service of worship in Béarn and publicly announced that it had “pleased the Lord to extricate me by his grace from the idolatry in which I was deeply mired, and to receive me into his church,” as she recalled later in her fascinating narrative, the “Ample Discourse”.

Three weeks later came a letter from Queen Elizabeth of England congratulating her on “her affection for the true religion.”

As the highest ranking Protestant in France, Jeanne became the leader of the Huguenot movement. She felt confident in God’s support for her and, frankly, in God’s promised help for her armies. She felt called to make her realm a homeland for the Bible-believing Christians of the Reformed faith. She recognized her own vocation in the stories of the Old Testament: she would thwart the prophets of Baal, raise the prophets of the Lord, and make safe the promised land for the beleaguered people of God.

The Loire River was the northern boundary of her territory, and as Reformed refugees crossed over it into safety, they thought of Israel crossing the Red Sea. They sang out Psalm 114, “When Israel went out of Egypt, the house of Jacob from a people of strange language; Judah was his sanctuary, and Israel his dominion.” Guyenne was the new Israel. Jeanne was the Lord’s anointed.

Jeanne sent Reformed pastors across her territories, imposed limitations on the practice of the Catholic faith, commissioned the translation of the New Testament into Basque and Béarnese, and established a Protestant seminary. She was denounced and threatened by Pope Pius IV and became the object of violent plots.

Religious hostilities escalated. Both Protestants and Catholics turned to condemnatory rhetoric, recriminations, conspiracies, vandalism, and marauding. Efforts towards peaceful coexistence faltered, and in 1562 the first French War of Religion exploded. Antoine chose the Catholic side, while Jeanne remained loyal to the Reformed Church, despite criticisms for disobeying her husband. Antoine sought to have his wife arrested and forced into a convent, but she was safe in her kingdom. Antoine died soon thereafter from wounds in battle. Jeanne was sorry.

Jeanne steered towards neutrality in the first two wars of religion, but with the third war in 1568, her kingdom was threatened with attack. She actively supported the Huguenot cause from the walled city of La Rochelle. She looked after refugees, rallied the troops, inspected the defences, and supported the military leadership of the brilliant Admiral Coligny.

Queen Jeanne died in 1572 of natural causes, though a rumour circulated that Catherine de’ Medici had poisoned her. A few months later the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, perhaps plotted by Catherine, decimated the Huguenot leadership, including Coligny.

Jeanne was succeeded in Navarre by her son Henry, also a committed Huguenot. In 1589 he would become King Henry IV of France, and he would end the eighth and final French War of Religion by granting religious liberty to Protestants in the Edict of Nantes of 1598.

But by then he had accepted Roman Catholicism. A cute but mischievous legend implies that he changed churches for somewhat epicurean reasons. The story goes that Catholic Paris refused to let him enter the city as a Protestant King, and as he prepared to receive the Catholic mass at the basilica of St-Denis in Paris in 1593, he was heard to say, “Paris vaut une messe”: Paris is well worth a mass. And I thoroughly understand the charms of Paris. But I don’t think that’s what was on his mind. He had learned from his amazingly strong, faithful, and brilliant mother and grandmother quite a bit about the mysteries of grace, and the duties of government, and the need for peace, and the fallibility of human judgment, and the vocation to serve God. To do what he needed to do as King of France required setting aside some personal predilections. And, after all, the religious landscape had changed over the past generation, and perhaps he considered that, whether in a reformed Catholicism or in a matured Protestantism, the same Jesus Christ could be adored and served.

Thomas Cranmer (1489 - 1556)

This biography is written by Professor Emeritus of Evangelism John Bowen. It also appears as the editorial of the October 16, 2017 edition of the Morning Star newsletter.

In 1533, Henry VIII was trying to find a way whereby the church might grant him an annulment of his marriage to his first wife, Catherine, who had failed to provide him with a male heir, so he would be free to marry his new love, Anne Boleyn. When Rome proved uncooperative, he “suddenly became alerted to the supposedly ancient truth that he was Supreme Head of the Church within his dominions.” (McCullough 193) Parliament obligingly passed the Act of Supremacy in confirmation of the king’s conviction, and on March 30th of that year, a certain Thomas Cranmer was installed as Archbishop of Canterbury, “swearing an oath that he would not allow his loyalty to the church to trump his loyalty to the king.” (Jacobs 9) Predictably, Cranmer declared shortly afterwards that Henry’s marriage to Catherine was null and void.

Who was this Thomas Cranmer? The first centre for the Reformation in England was the White Horse Tavern in Cambridge. (The house still stands but, sadly, it is no longer a tavern.) There, young men used to meet to discuss the revolutionary writings of Martin Luther, not least his direct approach to Scripture, his exposition of justification by faith, and his rejection of the sacred/secular split. Cranmer, then a student at Jesus College, was one of these young men.

Henry VIII was very conservative theologically—he found justification by faith to be a pernicious doctrine, for example—and he reacted strongly against Luther’s writings. Cranmer’s oath of loyalty to the king on the one hand, and his evangelical convictions on the other, meant he had to tread cautiously in implementing change.

However, during Henry’s reign, in 1538, “the government ordered that every parish in the country should purchase a Bible . . . in English, to be set up in every church, where the parishioners might most commodiously resort to the same and read it.” (Neill 55) This was a huge change since 1521, when church leaders had burned English Bibles in public. (Neill 70) Change was coming slowly.

Henry died in 1547, leaving the throne to his nine-year old son, Edward. He appears to have been moving in an evangelical direction before his death, having appointed evangelicals to significant positions of power (McCullough 247-248). He “can hardly have doubted what would happen immediately upon his own death” (Neill 61). As a result, with the accession of Edward, “the evangelicals found themselves with free rein to reshape the English church” (Jacobs 12), which they proceeded to do.

Thus “[o]n Easter Sunday 1548 . . . [Cranmer’s] English order for Communion became mandatory throughout England. The Latin Mass that had, in its various forms, been the only Mass in England for nearly a millennium was at that one stroke abolished.” (Jacobs 17) By the following year, Cranmer had produced the first English Prayer Book.

The use of this Prayer Book was enforced by law—the Act of Uniformity—in 1549. This was necessary because it was by no means welcomed with open arms. Eight of the eighteen bishops voted against it. Folk in the south-west of England joined in rebellion against the change, and 5,000 were slaughtered in reprisal. “Many Elizabethans were still Catholic at heart, and conformed only reluctantly to a church now bereft of spiritual comfort and external signs.” (Brian Cummings, in Jacobs 46) But it was not only traditional Catholics who rejected the new book. Some reformers had their own beefs with it: they “mocked even the use of the surplice . . .” (Jacobs 46) The evangelicals were also concerned about what they saw as the remnants of “papistry” in the book: the use of terms like “priest” (instead of presbyter or simply minister), “altar” (instead of Lord’s Table) and especially “Mass.” (Jacobs 48-49). Not surprisingly, 2,000 of the 2,700 words of the act concern penalties for not using the book!

A more radically Protestant version of the Prayer Book followed in 1552. However, King Edward died in 1553, and he was followed by Henry VIII’s older daughter, Mary, who was passionate for the old faith.

“Cranmer knew well what was coming” (Neill 90). By 1554, he was imprisoned in the Tower of London. Two years later, under “the pressure of argument with skilled exponents of contemporary Catholicism” (McCullough 274), “Cranmer’s nerve broke. He signed one recantation after another, each more degrading than the last” (Neill 94). In spite of his recantations, he was condemned to death. He was given the opportunity to speak one more time, in St Mary the Virgin Church (the University Church) in Oxfordand, to everyone’s surprise, used the occasion to withdraw his recantations. He walked from there to Broad Street, where he was burned at the stake. [1] He thrust his “unworthy right hand” which had signed the recantations, into the fire first. (McCullough 274)

So what is Cranmer’s legacy?

- Bishop Stephen Neill wrote that “[w]hen all is said and done, it was Cranmer who was the chief architect of the [English] Reformation” (Neill 67).

- Like other Reformers, Cranmer was passionate that Scripture and worship should be in the vernacular. This conviction is embodied in Article 24: “It is a thing plainly repugnant to the Word of God and the custom of the Primitive Church, to have publick Prayer in the Church, or to minister the Sacraments, in a tongue not understanded of the people.” That has become a cornerstone of missionary work and indeed of missiology—though it has not always been remembered either by liturgical conservatives or by prayer book revisers.

- Cranmer believed passionately that all Christians should get to know the whole of Scripture. His first Homily is entitled, “A fruitful exhortation to the reading of Holy Scripture” (1547). He regularized what we now call the Lectionary, so that “all the whole Bible (or the greatest part thereof) should be read over once in the year” (Cranmer’s words), so that Christians should be “stirred up to godliness” and enabled to “confute them that were adversaries of the truth” (in Jacobs 26-27).

- Cranmer’s Prayer Book has become the basis for all subsequent Anglican Prayer Books. “[V]ersions of it are used today in Christian churches all over the world, as far from England as South Africa, Singapore, and New Zealand.” (Jacobs 5) It is one of the things that unites Anglican churches worldwide.

How do Anglicans regard Cranmer today? I did a brief informal survey of some friends. Here is a sample of what they said:

- I am inspired by his vision to connect people to a worship life that is more relevant and user-friendly. Whether it is his emphasis on encouraging the faithful to engage more fully in corporate liturgy or in their private devotions (at home), these are important concepts today in our timely approaches to missional church. (A charismatic Anglican leader in Eastern Canada.)

- At nineteen, newly converted to faith in Jesus Christ, I found myself back in church one Sunday for a BCP service of Holy Communion. Suddenly Cranmer made profound and perfect sense. "Wow!" I remember thinking to myself, "The guy who wrote this was really saved!" All these years later, I might choose somewhat different language, but my appreciation has not lessened for the intense piety and clarity of theological vision with which Cranmer brings us to the table of the Lord. (A seminary professor—not at Wycliffe.)

- My formation as an Anglican was in the Book of Common Prayer. Over and over again, I find the phrases of the BCP rise up to meet me in daily situations, reminding me to ‘read, mark, learn and inwardly digest’ the Holy Scriptures;’ and naming my relationship with God, ‘unto whom all hearts be open, all desires known, and from whom no secrets are hid.’ (A bishop.)

The Anglican Communion commemorates Thomas Cranmer as a Reformation Martyr on March 21st, the anniversary of his death in 1556.

Bibliography

Jacobs, Alan, The Book of Common Prayer: A Bibliography (Princeton 2013)

McCullough, Diarmaid, The Reformation (Viking 2003)

Neill, Stephen, Anglicanism (Penguin 1958)

[1] There is some truth to the gibe that Cambridge produced the Reformers, and Oxford burned them at the stake.

William Tyndale: Servant of the Word (1494-1536)

This biography is written by Catherine Sider Hamilton. It also appears as the editorial of the October 30, 2017 edition of the Morning Star newsletter.

On (6) October, 1536, William Tyndale was strangled and burnt at the stake. The charge was heresy. Tyndale held that justification is by faith alone; he found no evidence in the NT of aural confession or penance; he insisted that in the NT the proper term for “priest” is “elder.” It probably did not help that he called into question the authority of the Pope and repeatedly railed against the corruption of the church (the clergy “are condemned by all the laws of God, who through falsehood and disguised hypocrisy have sought so great profit, so great riches, so great authority and so great liberties; and have so beggared the laymen, and so brought them into subjection and bondage, and so despised them” [The Obedience of a Christian Man]). But it was his English translation of the Bible that got him into trouble in the first place, and it is Tyndale’s Bible that is his lasting legacy.

Today, when the Bible has been translated into 636 languages and the New Testament into 1,442, it is hard to fathom the resistance to Tyndale’s work. But when Tyndale in 1522 approached the Bishop of London, Tunstall, for his support in translating the Bible, Tunstall refused. Tyndale believed—passionately—that everyone, plowman, king, baker, queen, should be able to read the Bible. Wycliffe’s 14th-century translation was officially prohibited; Nicholas Love’s Mirror of the Life of Christ was a sentimental and harmonizing paraphrase rather than a translation of the Gospels. “I had perceived by experience,” Tyndale wrote in his introduction to the Pentateuch, “how that it was impossible to stablish the lay people in any truth, except the scripture were plainly laid before their eyes in their mother tongue, that they might see the process, order, and meaning of the text.”The church, Tyndale said, had kept the Bible from the people, the better to impose on them its own law. Tyndale meant to give them the Bible, and to give them the best version possible. Whereas Wycliffe had only the Latin Vulgate on which to base his English version, Tyndale had Erasmus’ just-published Greek New Testament. Like Erasmus, whom he admired, Tyndale was an accomplished linguist: Latin, Greek, French, German, Italian and Spanish; in the last decade of his life he taught himself Hebrew in order to translate the Old Testament. And he had an ear for the power of English as the common people spoke it. His biographer Daniell notes repeatedly the force of Tyndale’s very Saxon English. The strong rhythms of the single syllables ring in the ear: “the poor, the maimed, the lame and the blind”; “And there fell fire from the Lord”; “and after the fire came a small still voice.” Tyndale wished to give the people a Bible in the words they spoke every day; he gave us a Bible for all the days.

Unable to win the Bishop of London’s patronage, Tyndale went to Europe. In 1526 he published, in Worms and then in Antwerp, a complete NT in English and smuggled it into England with the help of merchant ships. This contraband sold, apparently, like hot-cakes; one estimate has a print-run of 6000 (though 3000 is more probably correct, and still large). Tyndale’s promotion of Luther’s views, and his reforming translations (“assembly” instead of “church,” “elder” instead of “priest”) roused the ire of the churchmen; Bishop Tunstall condemned the book and made a public bonfire of it, and those who were found in possession of Tyndale’s bible paid dearly, arrested, fined, and tortured; some were burnt at the stake. Tyndale persisted, publishing in 1530 a translation of the Pentateuch from the Hebrew, in 1533 a study of the Sermon on the Mount, and in 1534 a second version of the NT. When he was betrayed and imprisoned, he was working to complete the translation of the OT—the first translation of the OT into English from Hebrew, Daniell notes, ever. It is still in many respects unsurpassed.

“Let there be lyghte”: this is Tyndale’s. “Am I my brother’s keeper?” “The Lord bless thee and keep thee. The Lord make his face to shine upon thee and be merciful unto thee. The Lord lift up his countenance upon thee, and give thee peace.” All Tyndale’s. “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” “We shall not all slepe, butt we shall all be changed, and that in a moment, and in the twincklynge of an eye, at the sound of the last trompe.” The twinkling of an eye! Paul says repeatedly “μὴ γένοιτο,” which translated literally means “may it not be.” Tyndale gives us “God forbid!” This is Paul in English: it is just right.

Tyndale was executed as a heretic in 1536, his NT still prohibited. Tradition has it that he said as he was tied to the stake, “Lord, open the king of England’s eyes.” Within two years, the King of England authorized an English Bible. It was called “Matthew’s Bible,” but it was almost entirely Tyndale. So, too, the Authorized Version (KJV)—and KJV is best where it follows Tyndale, because he used the Greek and Hebrew manuscripts. Our current translations still owe a great debt to him. Tyndale had a poet’s ear, and he loved the Word. It is this that comes through in his Bible. Again and again, it sings. “Though I speake with the tonges of men and angels, and yet had no love, I were even as soundynge brasse and as a tynklynge Cynball” (1526). Simeon’s song: “Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace.” Christ’s cry from the cross: “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” Forsaken, with its great sadness. And the Christmas story: “Behold, I bring you tidings of great joy, that shall come to all people. For to you is born this day in the city of David a saviour, which is Christ the Lord.” This day a saviour! It is the sound of a heart on fire.

Knox: A Name to be Proud of?

This biography is written by John Vissers, Principal and Professor of Historical Theology, Knox College. It also appears as the editorial of the November 20, 2017 edition of Wycliffe College's Morning Star newsletter.

At the May 2017 convocation of Knox College Professor Jane Dawson of the University of Edinburgh addressed the graduates with this friendly provocation: “Is Knox a name to be proud of?” For those who teach and study at the school that bears John Knox’s name – your Presbyterian partner in the TST, this is undoubtedly a more urgent question than it is for Wycliffe folks. But it is an important question for all who stand in the Reformation tradition. What are we to make of John Knox 500 years on?

As a start, it is generally agreed that Knox was the most important Protestant Reformer in sixteenth-century Scotland, prophetic, visionary, and a churchman through and through. He could also be manipulative and misogynistic, determined and domineering, and was often seen as strict and austere Through force of will and strength of voice, and often at great personal cost, Knox led a movement that reformed a church and reshaped a nation. But his legacy is complicated.

The basic facts about Knox’s life are generally known. He was born in 1514 or 1515 and died in 1572. After education in canon law at the University of St. Andrew’s, Knox was ordained deacon and priest in the late medieval Roman Catholic Church in Scotland and worked as a notary-priest. By the 1540s he was caught up in the movement to reform the Scottish church, largely through the example and influence of George Wishart.

This led to his imprisonment as a French galley slave (1547-1549) followed by exile to England where he served the royal court as chaplain and may have had some reforming influence on the text of the Book of Common Prayer. From England he fled to Frankfurt and then to Geneva where, under Calvin’s influence he discovered what he described as “the most perfect school of Christ that ever was in the earth since the days of the Apostles. In other places I confess Christ to be truly preached; but manner and religion to be so seriously reformed, I have not seen in any place beside”

Of course, not everyone in Calvin’s Geneva saw it that way but that’s not the point. Knox did and in 1559 he returned to Scotland to take hold of the Reformation there and the establishment of the Church of Scotland after the pattern he experienced in Geneva, Presbyterian in polity, and thoroughly Reformed in theology and liturgy. Knox died in Edinburgh in 1572.

In Scotland Knox was known as a powerful preacher who took the pulpit seriously as a platform for Christian truth and social change. Jane Dawson notes that “Unlike other Protestant Reformers such as Martin Bucer or John Calvin, Knox did not develop into a humanist scholar and linguist. But he did share the humanist celebration of the central importance of rhetoric.” And as a trained notary, he knew how to study texts carefully. He did not write much by way of theological treatises because by his own account his overriding task was to preach the gospel. In short, Knox exemplified the Reformation’s turn to the Word of God although he was more of a Biblicist than Luther and Calvin. Like Calvin, Knox expounded the Bible book by book, lectio continua.

As a preacher and Reformer, Knox had to navigate the social, political, cultural, national, and international issues of his day. He did so as a prophet, styling himself after the Old Testament figure Ezekiel, impatient with those who opposed what he saw as the truth of the gospel and its implications for the people of God. From Geneva in 1558 he wrote his infamous The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women, a polemical tract opposing the Roman Catholic queens of Scotland and England. To be sure, Knox worked with a Christendom mentality and the advent of a secular age like ours was beyond his imagination. But in his defense, he knew the gospel mattered for all of life, church and nation.

John Knox did not live an easy life and he was not always an easy person to be around. From recent records we now know that he was troubled by doubts, given to bouts of depression, even despair, and often lashed out. He was, to be sure a child of his time, and he ministered at a time when “clergy self-care” did not exist. So, we learn from Reformers like Knox the cost that Christian leadership often exacts.

That said, from all accounts Knox was a family man, committed to his wife and five children, with deep friendships and faithful colleagues. In 1909, on the 400th anniversary of Calvin’s birth, Knox was included on the Reformation Wall in Geneva where he stands alongside William Farel, John Calvin, and Theodore Beza, all who ministered in the Swiss City.

For those who wish to learn more about Knox’s life and legacy I recommend Jane Dawson’s excellent biography John Knox (Yale University Press, 2015). Dawson gives us a detailed, nuanced, and multifaceted picture of a leader described by reviewer Lucy Wooding as “a more complicated and laudable person; a loving husband, a steadfast friend, a fervent believer who was still frequently troubled by doubts, a brave fighter in the service of faith.”

A complicated legacy? Yes. A Reformer worth remembering? Yes. A name to be proud of? Yes, but only if we see John Knox for what he was: an earthen vessel with many flaws who was used by God for the renewal of the church in his time.