I was raised in a church and family that encouraged women to be all that they were meant to be. It was only when I started going to a church where women’s roles were restricted that I encountered pushback from the so-called silencing texts in 1 Timothy 2:11–12 and 1 Corinthians 14:34ff. Restrictions on what I could do and whom I could teach forced me to wrestle deeply with questions related to women’s roles in the church and family during my theological studies. I soon learned that the debate over women’s roles in the church had a very long history. What I didn’t know at that time was that our foremothers of faith had been active in this debate for millennia. Thanks to the hard work of many researchers, a growing number of works by silenced and forgotten women have been rediscovered, and their voices about Paul’s silencing texts can now speak again.

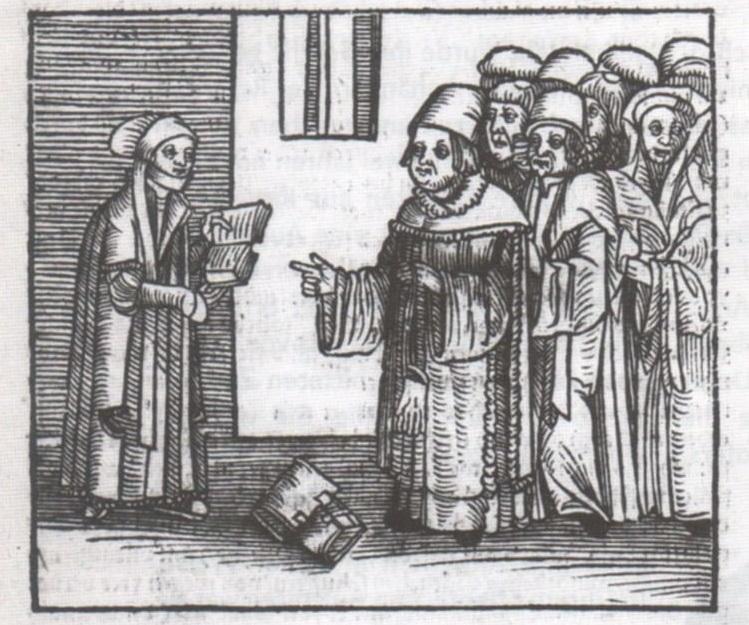

The boundary-pushing outspoken Lutheran Bavarian noblewoman Argula von Grumbach (ca. 1492– ca. 1554/7) was well known by her contemporaries for her refusal to keep silent, and she is now recognized as one of the major pamphleteers of the Reformation. Some 29,000 copies of the eight pamphlets Argula penned from 1523 to 1524 were distributed throughout Germany and into Switzerland. In her first published letter, Argula audaciously challenged the University of Ingolstadt’s theologians to a public debate about their abusive treatment of an eighteen-year-old Lutheran sympathizer.[1] In this letter, Argula references Paul’s directives in 1 Timothy 2:11–12 and 1 Corinthians 14:34ff regarding women’s keeping silence and not speaking in church.[2] Because no man dared to speak up against the injustices being done to the young university student, Argula felt constrained by the teachings of Scripture to speak out and correct her learned “brothers” for what she called their “foolish violence against the word of God.”[3]

Like other early women who dared to break silence, Argula defended herself by citing a mosaic of biblical texts, addressed to both men and women, that she believed authorized her to speak. Jesus’s instructions about confessing one’s faith before others (Matt 10:32; Luke 9:26), for example, compelled her to speak out against the sins of clerics and others in positions of power who were acting like the Pharisees of Jesus’s day and the hypocrites Isaiah had scorned:

You hypocrites! Isaiah was right when he prophesied about you:

‘These people honor me with their lips,

but their hearts are far from me.

They worship me in vain;

their teachings are merely human rules.’ (Matt 15:8; citing Isa 29:13)

Scriptural texts that describe an overturning of traditional hierarchies in the future also encouraged Argula to defy cultural and ecclesiastical traditions about women speaking. Had not the Psalmist declared that praise would come from the mouths of children and sucking infants [Psalm 8:2]? Had not Jesus said that things hidden from the wise and the greatest would be revealed by the Spirit and the Father to little ones, the weak, and the foolish [Luke 10:21; John 6:45 cf. Jer 31:34]? In her last published poem, Argula likened herself to the very stones that Jesus said would cry out if his disciples were to remain silent (Luke 19:40), and even to Balaam’s truth-telling ass (Num 22–24):

So save your breath, my dear Johannes,

From this example try to learn:

See what Baalam’s ass has done

God opened up that ass’s mouth

With human voice to speak the truth

The wise man Baalam to correct …

It’s not unlike the case today.[4]

Argula dared to speak, rebuke, and challenge Catholic authorities because she believed God was calling her to speak words of truth—not her words, but God’s word. She aligned herself with Paul who had confidently declared, “I am not ashamed of the gospel which is the power of God to salvation to those who believe” [Rom 1:16]. She embraced Jesus’s teaching to his disciples that he was sending them out like sheep among wolves, while assuring them that God’s Spirit would speak through them [Matthew 10:19]. The witness of these and so many other biblical texts convinced Argula von Grumbach that Paul’s teaching about the silencing of women in Corinth did not apply in every situation. And so, with confidence in her status as a baptized child of God speaking the word of God, she concludes:

What I have written to you is no woman’s chitchat, but the word of God;

And (I write) as a member of the Christian church, against which the gates of Hell cannot prevail.[5]

I am eternally grateful to Peter Matheson and others who arduously searched out, recovered, and translated the writings of Argula von Grumbach, whose voice once resounded across Europe, so that they can be heard again today. Argula von Grumbach dared to break the silence and challenge those she believed to have used their position and power to mistreat a young student in their efforts to stop the spread of reform in Germany. Argula believed that the larger witness of the story of God in Scripture pressured her to speak and so challenged the traditional universal application of Paul’s silencing texts.

I cannot and I will not cease

To speak at home and on the street.

As long as God will give me grace

I’ll tell my neighbour, face to face.

For Paul has not forbidden me,

Where God’s word cannot yet run free,

As sadly is with the case with us.[6]

May Argula von Grumbach’s now-audible voice continue to speak into ongoing debates about the Pauline texts being used still to silence women.

[1] Argula von Grumbach, To the University of Ingolstadt, in Argula von Grumbach: A Woman’s Voice in the Reformation, ed. and trans. Peter Matheson(Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1995), 91.

[2] Argula’s citation “because Paul says in first Timothy 2 ‘the women should keep silence, and should not speak up in church’” is likely from memory as she conflates 1 Timothy 2:11–12 and 1 Corinthians 14:34ff. Ibid., 79.

[3] Her letter also raises issues about the authority of Scripture, the need for church reform, and the freedom of speech and conscience. Argula’s defense begins with Jesus’s teaching about confessing him before others (Matthew 10:32–33). She also cites God’s promise that women will rule over his people (Isaiah 3:4, 12), Isaiah’s chastisement of those teaching the law in Isaiah 29, Ezekiel’s voicing of God’s promise to judge his people (Ezekiel 13:17, 19), the Psalmist’s promise “you have ordained praise out of the mouth of children and infants on account of your enemies” (Psalm 8:2), Jesus’s prayer of thanks that God has hidden these things from the wise and revealed them to little ones (Luke 10:21; John 6:45), Jeremiah 31:34’s promise that they will know God from the least to the greatest, Isaiah 54:13’s teaching that they will all be taught by God, Paul’s directive in 1 Corinthians 12:3 that no one can say Jesus without the spirit of God, and Jesus’s response to Peter’s confession: “flesh and blood has not revealed this to you but my heavenly father” (Matthew 16:17). Ibid., 76.

[4] Argula von Grumbach, An Answer in verse to a member of the University of Ingolstadt in response to a recent utterance of his which is printed below in the year of our Lord 1524,in Argula von Grumbach: A Woman’s Voice in the Reformation, ed. and trans. Peter Matheson, (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1995), 182.

[5] Argula von Grumbach, To the University of Ingolstadt, 90.

[6] Argula von Grumbach, An Answer in verse, 182.